The Facts Behind Mass Vaccination for COVID-19

Potential Strategies and Challenges

By Tabinda Burney and Andrew Rickles

Updated September 10, 2020

As the United States approaches the grim milestone of 200,000 deaths1 from COVID-19, a disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, researchers and drug manufacturers from around the globe are working together in an unprecedented effort to develop a vaccine to mitigate this greatest public health crisis in over a hundred years. Despite social distancing and stay-at-home orders instituted in the month of March, as well as guidance on wearing a mask and a phased approach to regional reopening, public health officials and leaders at all levels of government caution the public that a potentially more deadly second wave is likely to hit sooner than anticipated. This second wave could hit harder than expected due to a number of potential factors including what could be a premature rush to reopen, a rise in demonstrations and protests (where physical distancing and mask wearing may either be insufficient or lacking), or simply due to public fatigue toward the perception of the threat and resulting complacency.

Without a readily available COVID-19 vaccine, there is no way to curb the proliferation of the disease from the coasts to central parts of the country. The threat of the disease is most underscored in vulnerable communities, such as the Navajo Nation, which by May had been affected by higher infection rates per capita than either New York or New Jersey, two of the hardest-hit states at the time. The severity of the COVID-19 disease and the fragility of healthcare delivery in these underserved communities could be further exacerbated by the impending flu season this fall. The surge of the flu and COVID-19 would compound conditions, making recovery in these communities next to impossible. To successfully combat this novel coronavirus pandemic, a gamut of options must be considered, with solutions that are safe, effective, timely, cost-effective, and reproducible.

Potential Strategies

There are several strategies to combat the current COVID-19 threat in the United States, which can be employed in compliance with our scientific understanding of virology and infectious disease behavior and our historical experiences with influenza, coronaviruses, and other highly infectious and communicable diseases. Perhaps the most ubiquitous strategy in the media is pre-exposure prophylactics, or drugs that are used as preventative measures by people who have not yet been exposed to a disease. Pre-exposure prophylactics include both drugs and vaccinations that are provided to those most at risk of contracting the disease.

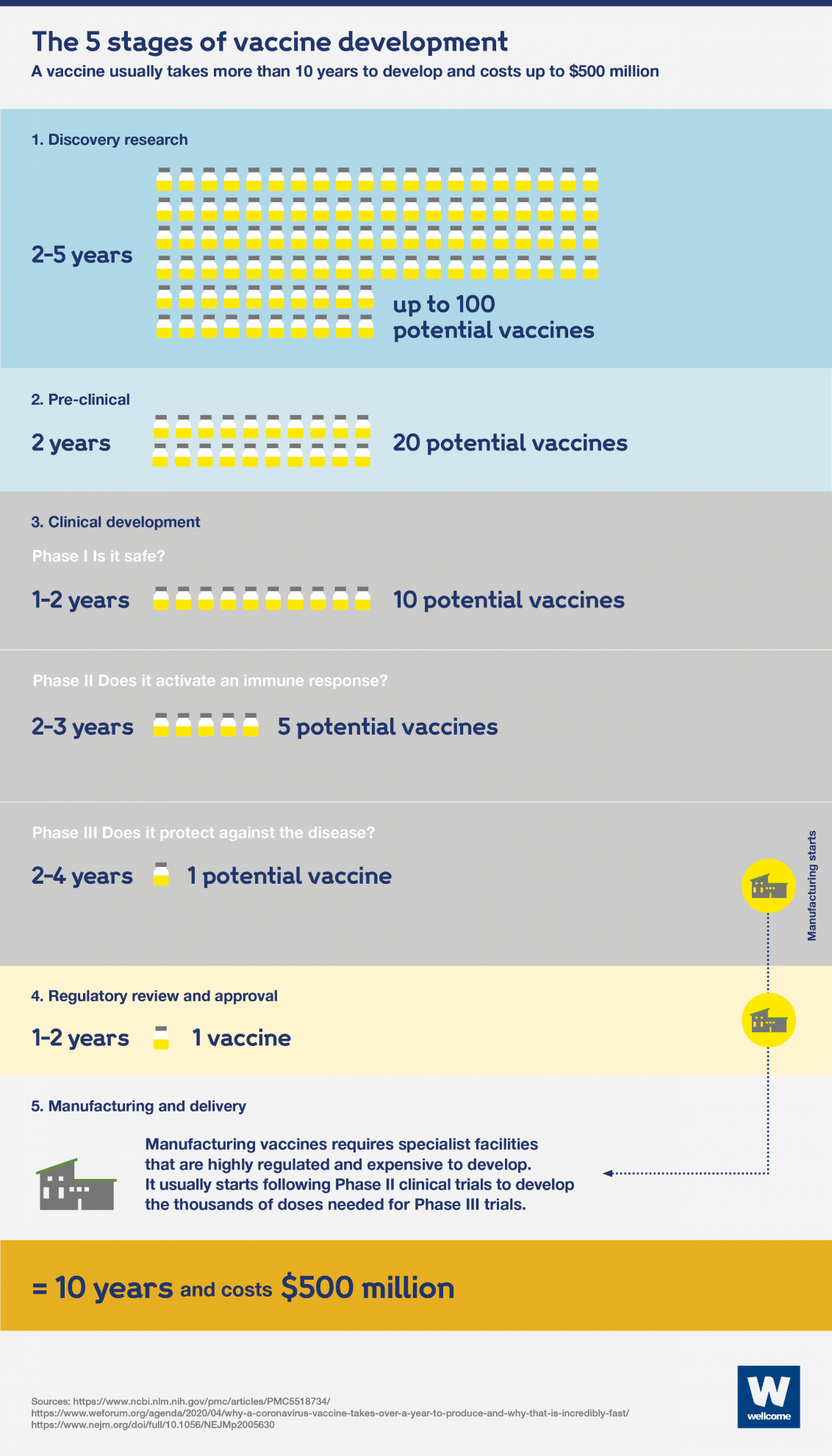

Another critical component of the fight against COVID-19 is the development of a vaccine to immunize the entire U.S. population. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provide the following definition: “Vaccines contain the same germs that cause disease. But they have been either killed or weakened to the point that they don’t make you sick.” When these less potent remnants of the disease are injected into the human body, they activate the immune system into producing antibodies to recognize and kill off the germs if the potent, living version ever infects the individual. This strategy, though highly effective, is expensive and normally requires a lengthy research and development process. Due to the pressing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is currently executing Operation Warp Speed, designed to reduce the amount of time traditionally required for the linear sequence of events in the vaccine development process.

Public health and medical experts also stress the importance of post-exposure prophylactics, or drugs that are administered after disease exposure. In most cases, these drugs are meant to shorten the recovery time of an individual after they contract COVID-19, much like Tamiflu for seasonal flu. Although drugs like hydroxychloroquine-and more recently the steroid dexamethasone–have shown some positive results anecdotally, there have not been extensive enough randomized clinical trials to justify using these drugs widely.

To date, there are few Food and Drug Administration-approved therapeutics or treatments for people infected with COVID-19. The FDA has granted an Emergency Use Authorization for the administration of antibody treatments with convalescent plasma, but many scientists believe that its effectiveness cannot truly be measured without randomized clinical trials. Research and development efforts are continuing to push studies on the effectiveness of existing anti-virals. Ordinarily, the process of drug and device approval for medical use is lengthy and involves several testing trials. However, the Food and Drug Administration does have the authority under its Emergency Use Authorization to allow for the use of unapproved medical products to treat life-threatening diseases or conditions where there are no adequate, approved, or available alternatives. There is a growing list of Emergency Use Authorization drugs and tests on the current Food and Drug Administration.

Top Challenges Facing COVID-19 Vaccine Development and Distribution

With vaccines being the most promising strategy to both reduce the case rates of COVID-19 and develop population-wide immunity, many companies are investing in this intervention and are well into the research and development phase of an effective vaccine. Along the way they have faced and will encounter additional challenges that could result in a delay in administering the vaccine to the over eight billion people who require it worldwide. Here are some of the many challenges (in chronological order):

1. Undesired immune response

During prior vaccine development activities against respiratory viruses, scientists have observed several undesirable responses in experimental animals. In some cases, the animals developed an inflammatory response in their lungs. In other cases, a different type of response occurred involving antibodies (produced as a normal immune response to the presence of foreign viruses) that bind to the virus and help it to replicate. These problems can arise when developing any vaccine, but because this is a novel coronavirus, these complications are of even greater concern.

2. Pre-clinical challenge testing

Before human trials can take place, potential vaccines must be tested on laboratory animals. With SARS-CoV-2, this has been difficult because very few animals are susceptible to the virus. Scientists were able to carry out the tests on rhesus macaques, a type of monkey originating in India.

3. Massive-scale production

Given the extremely large number of people worldwide who will need the vaccine, production capacity is a real concern. Manufacturers will have to scale up production even before a vaccine has been fully tested and approved. This obviously presents a risk for the manufacturers, which has been offset through the Defense Production Act that guarantees them payment. Additionally, even with preemptive production, one manufacturer will not be able to provide enough vaccines for the entire world. Multiple vaccines will need to be produced and distributed simultaneously to meet demand, raising additional concern about equitable distribution around the world.

The five stages of vaccine development. Source: https://wellcome.ac.uk/news/how-can-we-develop-covid-19-vaccine-quickly

4. Cold-chain process (transportation and storage)

Vaccines are extremely fragile between the time they are manufactured and the time they are administered to a patient. Vaccines should be stored and transported between 2°C and 8°C (35°F and 46°F). If the temperature varies too greatly, the vaccine can die and become inactive and ineffective. Given the distance the COVID-19 vaccine may have to travel, this is a real concern.

5. Supply chain shortages

The world does not have enough glass vials to store and administer the vaccine, or the capacity to fill those vials. The type of glass used to manufacture these vials makes up just 10 percent of the glass produced. It is also more expensive to produce. On June 9, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services awarded a $204 million grant to Corning Incorporated to make these vials.

6. Distribution

Once the vaccine is mass produced and made available nationally, it must be deployed to the public quickly and efficiently. As part of routine pandemic planning and exercising, state, local, tribal, and territorial health officials must determine their normal and emergency medical supply chain mechanisms, develop multi-pronged distribution strategies that may involve local logistics/carriers (including UPS, FedEx, and the U.S. Postal Service), or drone technology, and identify locations where they can receive, stage, and distribute additional vaccines delivered by the federal government to augment their supplies. In addition, the distribution plans that are developed must include clear communication about the safety and efficacy of the vaccines to ensure that information is correctly relayed to the public, which may be apprehensive about receiving a new vaccine. The Strategic National Stockpile at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services stores medicine and supplies for emergencies at various locations around the country that can be deployed within 12 hours upon request, and can be utilized by state, local, tribal, and territorial health officials to supplement their existing plans and resources.

7. Prioritization

It is simply not possible to produce the nearly eight billion doses of vaccine that the world will require. The CDC will issue guidelines regarding who will receive the vaccine first. State and local health departments will make the ultimate decision about who gets vaccinated, based on these guidelines. The top tier may include healthcare workers and first responders and likely the elderly and sickest patients who are at greatest risk of dying from the disease. Many of the disadvantaged communities who have been hit hardest by COVID-19 could be left out-predominantly communities with greater percentages of people of color. Additionally, though it makes sense to deprioritize vaccinations for those who have the flexibility to work from home and social distance, this group is not likely to accept being deprioritized.

In response to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, the CDC developed guidance for allocating and targeting vaccines during a pandemic. Their overarching goal is to vaccinate all people in the United States who choose to be vaccinated, prior to the peak of the disease. However, this timeline is not always possible and in the case of vaccine shortages, a prioritization scheme must be developed. Prioritization should be based on vaccine supply, pandemic severity and impact, the potential for disruption of community critical infrastructure, operational considerations, and publicly articulated pandemic vaccination program objectives and principles. Specifically, the vaccine priority should protect those who will maintain homeland and national security, are essential to the pandemic response and provide care for persons who are ill, maintain essential community services, are at greater risk of infection due to their job, and who are most medically vulnerable to severe illness, such as young children and pregnant women.

8. Administration

Even after surmounting the distribution and prioritization challenges, administering a vaccine to such a vast cohort will require novel and innovative strategies. It will likely require many partners to get the vaccine to as many people as possible, as quickly as possible. At an Institute of Medicine Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events in 2010, Lisa Koonin from the CDC noted, “The private sector can’t do this alone. Government cannot do this alone. It really is necessary to leverage the unique talents and capabilities of a wide variety of partners, essentially at a community level, to make this work.”

Lessons learned from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic indicate that theses partners could include locally run department of public health mass vaccination clinics, private-sector contract immunizers, emergency medical service providers, school vaccination programs, college student health clinics, healthcare providers, pharmacies, and even occupational health clinics at some large corporations. Participants at the forum noted that it is necessary to integrate the private sector for a successful vaccine program because this sector has access to thousands of employees and their families. Their participation can also lessen the burden on an already overtaxed public health system.

In the Meanwhile, Social Distancing Remains Critical

As the world slowly begins to reopen after months of lockdown, the safety and health of those returning to work and reentering their communities is of utmost concern. Many scientists predicted that a premature opening of communities would result in a resurgence of the virus: Dr. Anthony Fauci warned that the United States could face even more “suffering and death” from the coronavirus if some states rush to reopen businesses too early-a statement that has already proven to be true in many communities. In addition to the surge of cases in the United States in recent weeks, scientists have also predicted a likely second wave of the virus to occur globally sometime this fall that will require the world to go back into lockdown to prevent mass infection. It will only be truly safe to return to normal once a vaccine has been developed and distributed to all who need it.

At the time of this publication, the vaccine development process is entering Phase 3 of the clinical trials. Reports indicate that a COVID-19 vaccine may be available as early as the beginning of 2021, but as discussed, it will likely take several additional months until that vaccine is available to the general public. During the interim, it is critical that social distancing be maintained and that communities maintain responsible practices to prevent the further spread of COVID-19.

[1] This is the death count at the time of this publication (September 10, 2020).